Updated Editor's Note: In 2015, Timbers.com commissioned a special series of articles with Howler Magazine that explored the community and culture of Portland soccer. Among the stories was this special oral history of former Timbers NASL great, longtime University of Portland coach and American soccer pioneer Clive Charles. Read it to learn more about the legend and legacy of a one-of-a-kind Timbers personality.

Editor’s note: This season, Timbers.com and Howler Magazine have collaborated on a special series that explores soccer in Portland and the city’s influence on the game in the United States. Presenting our fifth story in the series, we tell an oral history of one of the most influential Portland Timbers players of all: Clive Charles.

------------

"There wouldn’t be soccer where we are today out here if it wasn’t for Clive, in my opinion,” says Harry Merlo, former owner of the NASL Portland Timbers, University of Portland soccer booster, and a guy who ought to know.

Clive Charles was a Timbers defender, University of Portland men’s and women’s soccer head coach, manager of the U.S. Olympic squad and also a mentor to thousands of players who passed through his teams.

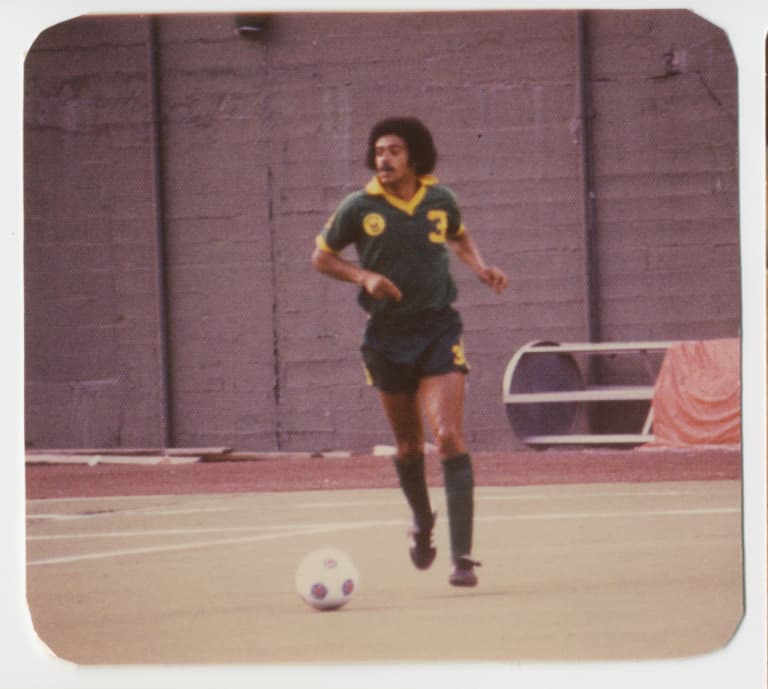

Born in East London in 1951 as one of nine children, Charles got his start as a player at the West Ham United academy when he was 15. Moving through the ranks to the first team, he went on loan to the NASL’s Montréal Olympique at age 20.

While in Québec, Charles caught the eye of Clarena, a flight attendant in training who was staying at the same team hotel in Montréal. They married, and when Charles went to play for Cardiff City, Clarena went with him. Longing for a return to North America, the couple came back to North America when Charles signed with the relatively new Portland Timbers in 1978.

Charles played 67 games with Portland in the NASL—plus another nine in the NASL’s indoor league—before moving on to play with clubs in Pittsburgh and Los Angeles. But there was something about the City of Roses that connected with Charles, so much so that the family settled there permanently at the end of his playing days.

He had a combined 439-144-44 record at the University of Portland and was one of five NCAA coaches to win more than 400 soccer games. He led the Pilots women to the 2002 NCAA College Cup title. He started a youth soccer club, FC Portland, that still operates today and is one of the strongest youth clubs in the Northwest. He coached the U.S. Men’s National Team in the 2000 Summer Olympic Games in Sydney to the semifinals—its highest finish ever in the competition.

Ask anyone who had the good fortune to play under him and you’ll hear about Charles’s soccer knowledge and love of the game—and you’ll hear even more about his love of life. To him, soccer was merely a catalyst to help make one a better human.

Charles was well-regarded during his 17-year playing career, but it was his work with the youth, high school, and college players of Portland and beyond in the years after his retirement that, perhaps more than anything else, set a lasting foundation for Portland’s place in the American soccer scene.

------------

1978: Portland, Oregon—Not Maine!

Clarena Charles (Clive’s wife of 30 years and the mother of their two children): The Timbers offered him a contract. Having played in Montréal, and myself being Canadian, he had decided that he would like to get back to playing in the U.S. or Canada. I thought it was Portland, Maine, which was close to home [in Montréal]. We were very excited about that until someone said, “No. It’s Oregon.” We had to get the atlas out and look where Portland, Oregon, was and then realized it was on the West Coast.

John Bain (Timbers teammate, assistant at University of Portland): We used to go to Elmer’s in Beaverton for lunch every day—the whole team used to go after practice—and Clive and a guy called Graham Day, they, basically, were the comedians.

Timber Jim (Longtime Timbers mascot in the NASL and USL eras): We were at a picnic on the Clackamas River. People start talking, saying that we should be doing this or that. I made a remark about, “Man, when are we going to stop sending the long balls in? Is [manager] Don [Megson] taking the team in the right direction?” Clive thought for a second, and he goes, “Well Jim, if I thought he was doing a bad job I would talk to him about it, but I wouldn’t talk to you about it.” And he was right.

Clarena: The Timbers set us up with an apartment and some cars, everything we needed. Clive returned home from one of the first practices with season tickets. We’d never had season tickets. In Europe it wasn’t a tradition at that time for families or wives to go to the games. It was a job. This is how my children and myself really got introduced to the game and watching him play, because I had probably only ever seen him maybe twice.

Bain: Clive was a left fullback. Most fullbacks were just aggressive, very physical, and they would just kick you. But Clive was an overlapping fullback. He was like a modern day fullback. He was a player before his time, almost like a left winger. Clive was a fantastic player, and I think that sometimes that gets overshadowed because he was such a great coach.

1983: Return to Portland

After stints with the Pittsburgh Spirit and Los Angeles Lazers indoor teams, Charles retired in 1983 and immediately moved his family back to Portland, where they still had a home and many friends. He didn’t have a job lined up, but word spread that a former Timbers star had returned to town, and Charles received a phone call from former NASL Timbers teammate (and future fellow Timbers Ring of Honor member) Jimmy Conway who told him of a head coaching gig at a Portland high school.

Clarena: We really liked Portland right from the very beginning. When he was moving, transferring leagues, indoor, outdoor, we always returned to Portland, to the same neighborhood. Clive decided to retire, and when he returned here, he was offered the Reynolds [High School] job.

Clarena: Clive never brought soccer home. He would leave home, do his job, and come back and be a dad. He did realize that the pool of players and the standard of play was lacking in Oregon. That’s when he started the FC Portland Academy. It was a summer program to develop high school players, expose them to a higher level, and then give him a larger pool to recruit for the university.

FC Portland grew into one of the most respected youth clubs in Oregon, and featured future University of Portland stars as well as pro players. But wherever Charles coached, be it at the youth, college or national team level, he introduced discipline, although never heavy-handedly.

Clarena: At West Ham, the younger apprentices had to clean up after the older players. They had to clean their boots and they had to clean the locker room and they had to clean the bathrooms.

He realized how hard people that the players don’t see have to work so hard to keep the stadium clean, to keep the locker room clean. And so when he started working with the kids, he said it’s not fair to have people picking up after you when you are perfectly capable of doing it yourself.

So that’s what started all of that about; tuck your shirt in, clean your boots, make sure you have everything. Pick up your tape and your mess off the field. And it was part of a development to complete the person to think of others, not just yourself.

Bernie Fagan (NASL Timbers teammate and head coach at Warner Pacific College in Portland): When the Timbers folded, a lot of former Timbers were wondering what we were going to do. I was fortunate enough to get the Warner Pacific job in 1983. At that time it was actually a decent wage, I think $24,000. About nine months later, after the first season, the University of Portland fired their coach. Harry Merlo wanted me to be the coach at the University of Portland. They offered me $18,000. I said, “I can’t take this job.” So I called Clive. He obviously did a fantastic job at UP, but it could have been me. It would have been me if I’d said, “Yeah.” But those $6,000.…

1986: Building a dynasty from the ground up

After three years at Reynolds, Charles was offered the UP men’s head coaching job, after Fagan reportedly turned it down. At the time, UP was a small and athletically quiet school. And then Charles arrived.

Kasey Keller (University of Portland goalkeeper, USMNT veteran): I was being recruited by all the big names, and the University of Portland was this little school that really hadn’t made much of a name for itself yet. But the draw of being with Clive, and understanding my goal was to be a pro—you just realize, “This guy is going to be the best person for my career and I just need go to University of Portland and spend more time with Clive Charles.”

In 1989, Charles took on the women’s head coaching job as well, which he would hold simultaneously with the men’s job for the remainder of his career. Somehow.

Tiffeny Milbrett, (FC Portland youth player, University of Portland forward, USWNT veteran): I didn’t need to be on the number one team in the world. Getting to the highest level, there’s such an individual journey. He just assured me that he was going to do the best that he could for me. He had already built the guy side of it and he wanted to do it for the girl’s side. It was a no-brainer to continue to learn from one of the geniuses of the game.

Christine Sinclair (Thorns FC forward, played under Charles 2001–05 at UP, where she was twice named national player of the year): My family knew Clive my whole life. My uncles [Brian and Bruce Gant] played professionally with him. Being recruited, I had narrowed it down to UP, North Carolina, Nebraska and Connecticut. He was the only coach of the four that actually didn’t care about the soccer, in a sense. He cared about what I wanted to do after soccer, if soccer didn’t pan out the way I hoped, and he cared about me fitting in at a school.

Keller: I come back from the U-20 World Cup, I win a Silver Ball, I’m starting to get some interest from some clubs in Europe. And Clive didn’t say, “Well no, we’ve got something started here at the school and we’ve got chances to win national championships.” He said, “Let’s look at each individual situation, we’ll make some phone calls and if it’s right, it’s right, and we’ll come to that conclusion together.”

Bain: He just knew how to put things across and to talk to people.

Keller: There was no way that I would have had the career that I had if I hadn’t have made the decision to go to University of Portland. I was so ready when I got to Millwall.

Sinclair: You just respect him right off the bat. He has this presence about him. But he wasn’t lying when he was recruiting. He was all about you succeeding as a person first. I’ll never forget, one thing he said, he’s like, “Yeah, I’ve had some great players come through the program like Tiffeny Milbrett, Shannon MacMillan, and they’ve gone on to have incredible careers but,” he’s like, “they were already stars when they got to UP.” And he’s like, “I don’t pride myself on them.” He’s like, “I pride myself on what I can do for the worst person or the worst player that comes in as a freshman and where they’re career goes.” I’ll never forget that. UP is a school, but it’s like a professional environment. You do the little things right.

- Howler x Timbers: Thorns FC's well established place in Soccer City, USA and beyond

Harry Merlo (lumber baron, former NASL Timbers owner, and UP soccer booster): Clive won the National Championship for the University of Portland, and I built the beautiful Merlo Field in his honor. I would have never built it without him.

Milbrett: He would just love to chew gum. He always chewed gum. And there was a garbage can, oh, I’d say 30 yards away, and he turned to one of the players and he goes, “Hey, I’ll bet you a dollar that I can make it into this garbage can.” Of course everyone’s thinking, “Oh yeah, good luck, 30 feet away.” So what does he do? He starts walking toward the garbage can. He gets right up close and he puts the gum in garbage can. And everybody’s like, “Oh, come on!” He’s like, “No. You never said I had to try from 30 yards away. You just assumed. I made it. You owe me a buck.”

Clarena: He was interested in [students’] parents and their life, where they were going, their studies, what they were doing. So he was continuously encouraging them to grow, to develop. It was always a pleasure to watch a freshman come in and then four years later the change in that person. He was heavily involved with them. He was interested in everything that they were doing so it was like taking in another family member. Only there was 50 of them every year.

There was a tradition that the University of Portland that when the season began, everybody came to my house for a barbecue, or throughout the season they would come in as a group. And then I also managed the summer soccer camps at the University of Portland. So we employed many of the players. And so I got to know them really, really well. All the time Clive was coaching at all the levels I was lucky to be able to share.

Milbrett: I’ve been coaching now for six years, and it’s just that they all look the same. All the players seemingly are just grown and developed the same. Clive didn’t like that. He embraced everybody’s personality, individuality. I remember him always saying, “Gosh, if you want great players, you’ve got to learn how to manage their crazy personalities.”

Milbrett: He didn’t care about mistakes. Too many coaches yell at players for mistakes—especially young players. It just doesn’t make any sense. He never did that.

1993: National teams take notice

Through his successes at UP with both men’s and women’s programs making it to the NCAA tournament, Charles’ influence on the national game grew. He coached the U.S. U-20 Women’s National Team from 1993-1995 and was an assistant on the U.S. Men’s National team at the 1998 FIFA World Cup in France.

Charles was the head coach for the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney, where he led a loaded U.S. Men’s U-23s team that included Landon Donovan, Frankie Hejduk, Brad Friedel, Tim Howard, and captain Brian Dunseth, who would name his son Micah Clive after the coach. Charles had been diagnosed with cancer before the games, but very few people knew outside of his family. The team made it to the semifinals—the furthest the U.S. had ever progressed in the tournament—and lost 2–0 in the bronze medal game to Chile._

Brian Dunseth: The guys would say, “Dunny, go ask for a night out.” So I’d say, “Hey Clive, the boys want a night out.” And he always just told me, “All right, cool, have fun. I don’t care what time you get back, just make sure at 10 o’clock in training, everyone does the business so you can have the opportunity again.” He kind of set the standard that, yeah, you can go out, you can drink, you can have fun, you can party, you can try to hook up with girls—you can live life outside of the game, but when I blow that whistle for training, it’s time to put in work.

Dunseth: [Later, when] everyone else is finishing up the training session, he’s on the other side of the field, just slowly walking with a player and having a conversation. He just found these really intimate moments where in a helter-skelter environment he could figure out psychologically what was going on with his players to, I think, maximize the talent that he had available while still making it feel like it was not about soccer.

Dunseth: Throughout the two and a half years that we were together at the Olympic team, he had taught us so well tactically how to play a diamond formation that he could sit on the bench and regardless of which team we were playing, if they switch formation—if they were playing a 3-5-2, a 4-4-2, whatever they were playing, 4-3-3, we knew how to play against whatever formation because we’d been together so long and he had taught us how to make adjustments on the fly.

Clarena: It was exciting. It was the biggest venue I’d ever been at. It’s always flattering when you go somewhere and people are saying, “Oh, there’s the U.S. team,” you know. There’s an excitement, anticipation. The players want the games to start so they see where they place and how they manage. So yeah, it was a little bit of intrigue. It just created a not-like-home environment. It wasn’t a big party but it was an exciting time, and it was catching. And that was with all the different countries and all the different teams.

Dunseth: I mean you look at 2002 [World Cup] and the run that Bruce [Arena] made, I think there’s a handful of guys out of our Olympic team that slid in pretty seamlessly into Bruce’s starting XI.

Clarena: Our son couldn’t go but our daughter did go with us, and we were able to stay in the same hotels. We didn’t know how long we had, so it was a very emotional time for us. Fortunately when he came back things started to work. And throughout that whole process I so much wanted him to be happy.

2002: A special victory

After a series of treatments, Charles was still coaching when the 2002 collegiate season began. His women’s team, by now knowing he was ill, reached the NCAA College Cup championship game held in Austin, Texas.

Clarena: With the illness I knew he was running out of time, and he did too. The year prior we [lost to North Carolina] and then this was another chance in Texas.

Sinclair: I think of our practice the day before that final. He goes, “Everyone take your cleats off.” And then they piled all our shoes in a pile. He had us line up at the sideline and we did a shoe toss. There was a bet who could throw their shoe farthest. And that was practice. He’s like, “Okay, let’s go win tomorrow.” I honestly think a third of the team that played the final were not in their own cleats.

Sinclair: It was never about him. But there was one instance where—it’s on tape—where he’s like, “Go out there and have fun. And if you have fun, you’ll win, and you’ll make me a very happy man.” It was the first time he had brought himself into it at all.

UP won a national championship that year beating rival Santa Clara 2-1 in a come-from-behind, 2-1 victory in double-overtime. Sinclair scored both goals in the championship.

Clarena: Oh, it meant everything. That was his top goal for the University of Portland. It was a commitment that he had made to the major supporters, the Earle Chiles, the Harry Merlos, that was part of his platform. That when he was hired he said, “I will bring a national championship to Portland.” And to win it—it was just so sweet.

Sinclair: It was all about succeeding for him and winning it for him. Obviously we didn’t know what the outcome was going to be with his illness, but that season was all about winning it for him. Peaking at the right time to do it.

Epilogue: Clive Charles and Soccer City, USA

Clive Charles passed away at his Northwest Portland home in August of 2003. He was 51 years old. To this day, Charles’ number three is the only one to have ever been retired in Timbers history. But his legacy looms far larger than that.

Sinclair: Those that have been influenced by him and impacted by him refuse to let his story die. I know for me I’m going to go into coaching and I’m going to pass on the lessons that I learned from Clive to whomever I coach. So I think like in a trickle-down, he’ll impact the whole game sooner than later.

Keller: Clive’s at the house, and all I have is a bottle of Johnnie Walker Blue Label, which is about $200 a bottle. And Clive’s drinking whiskey and Coke, and I’m watching this brand new bottle of Johnnie Walker Blue Label get diminished by mixing it with Coke. And I’m having a heart attack, but it’s Clive. If Clive wants to drink my Blue Label with Coke, then he can drink my Blue Label with Coke.

Milbrett: Who else was able to build what he built and get the support and just the magic around it? It’s like this little aura bubble, is what he was able to do.

Dunseth: I often say that he taught me more about the game than anyone ever had, but he taught me more about being a man. The impact that he had on the individual’s life was pretty astonishing, considering he was, “just a soccer coach.”

Keller: People like Clive at the end of NASL sticking around and really jumping into the community and showing people that this sport is healthy, and can be something in the future, it’s so much a part of Portland’s claim as Soccer City, USA. Even though I would joke that it’s still about a 180 miles north—but it is down to the commitment that Clive Charles had to stay in Portland and be such a huge inspiration.

Clarena: Development. That was his goal. That was what he wanted. He wanted to make soccer better in Portland, in Oregon, in the U.S., and have them be able to compete at each level nationally or internationally.

Clarena: He lived and breathed coaching. He would sit indoors, and find a little scrap of paper and be working out team moves for each different team at each different level. He was continuously dabbling and thinking about, “Oh, this player could move here, and this and that.”

He lived and breathed soccer at all levels. He wrote down once, “Never want to win more than your players.” He enjoyed their success as much as they did. In that sense, he was very, very satisfied.

------------

About the Authors:

Brian Costello is the director of digital media and editor in chief for the Portland Timbers and Thorns FC. He has previously written for This is American Soccer and The Portland Mercury.

Leander Schaerlaeckens is a freelance writer. He was previously a soccer scribe for ESPN.com and FOXsports.com and has also written for the New York Times, ESPN The Magazine, the Guardian and many other places

About the Illustrator:

Designer and artist Nick Iluzada has created work for Bumpy Pitch, GQ, Howler Magazine, Newsweek, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and Wired.