The street names 76th and Yamhill are recognizable to those with even casual knowledge of Portland, but the place where those streets meet in the city’s southeast quadrant could pass for most Rose City neighborhoods. A small market a block away is one of the neighborhood’s few merchants west of the East 82nd’s business district, with the bars and cafes of East Belmont providing the area’s next closest murmurs. It’s solemn houses with small front yards that define this part of the city, with build dates stretching back multiple generations making the secluded blocks ideal for first-time buyers and entrenched Portlanders, alike.

It’s only right that Dennis O’Meara, a man whose life was also poignant, if relatively secluded, will be celebrated in that part of the city on Thursday, even if, for those close to the quiet icon, those celebrations will still be painful. On February 16, the 68-year-old suffered a sudden and tragic cardiac arrest, leaving those closest to him mourning a life taken too soon. His last respects will be paid at 76th and Yamhill, at Ascension Catholic Church at noon, in a neighborhood as quiet and modest as O’Meara’s accomplishments.

That many reading this, in this location, were likely unaware of O’Meara will be surprising when you consider his contributions to soccer. He was the first public relations director in Portland Timbers history, serving as part of the club’s initial front office in capacities that far exceeded his title. From 1974-78, he was the men’s head coach at the University of Portland, helping found and grow the school’s program from a club team to its varsity status. Similar impacts at his alma mater, Portland State University, as well as working at local high schools and clubs, extended O’Meara’s influence beyond Goose Hollow and The Bluff.

No part of what we love about Portland soccer would be as prominent today without Dennis O’Meara. Not at the professional level. Not at the collegiate or youth levels, either. Long before his passing, his legend should have already been told.

-----------

“He would have been 23, 24 years of age,” remembered Timbers original Mick Hoban, one of four people whose names hanging in Providence Park’s Ring of Honor. As a 23-year-old, Hoban was one of the first players to arrive with the 1975 team, with the hastily-organized squad gravitating to the Rose City in late April. By then, O’Meara (23, at the time) had already been in his job for four months, serving as one of the skeleton crew tasked with bringing the North American Soccer League to Portland.

“What people may forget, or may not even know, is starting in early January before the season opener May 12, there were five employees in the Portland Timbers’ office,” Hoban explained. “Dennis was one of them, and Dennis was the only employee at that time with any experience in soccer.”

Gus Proano, a local doctor, was the driving force in securing the Timbers’ financing, Hoban remembered, while Don Paul brought National Football League experience to the team’s general manager’s role. “He could sell snow to the eskimos,” Hoban said of Paul, but as far as soccer knowledge? Only one person in management had any, let alone the connections O’Meara would leverage to make that knowledge work.

“He was your go-to for anything that required doing locally, whether is was finding training facilities, working out tryouts, finding transportation, accommodations for the incoming players,” Hoban recalled. “He was helpful in all of those pieces.

“He was a jack of all trades and a master of many. He became the guy you’d go to with any form of question. ‘Where do I take my driving test?’ ‘Do you know anybody that could,’ and fill in the blanks.”

As Vic Crowe, the Timbers’ first head coach, was in the United Kingdom recruiting for the Timbers’ first team, O’Meara was the focal point in Portland. Find a player, hand them off to Dennis. This is how the city’s NASL first team was formed, and as players came into market, it was O’Meara that helped get the team’s first stars out in the community, trying to promote Portland’s next professional sport.

“I was the first player in town,” Hoban remembered, about 1975. “I arrived on the 10th, and the rest of the players, I believe, arrived on about the 27th – we’re talking April, now, before a May 2 kickoff. I traveled with Dennis to various Rotary, Kiwanis, all the service clubs. To school assemblies, you name it.

“Anybody that made a request, we were right there, pounding the pavement, to try and introduce the club, the sport, sell season tickets. Dennis would drive me to various locations and give me the background on each of the organizations so I didn’t look a fool, wondering what the Lions was or the Kiwanis – which I didn’t know, coming from the UK.”

Tony Betts was in that situation, too. Another original Timbers player, the Derby-born forward arrived in Oregon from Aston Villa as a 21-year-old and quickly become a face for a new movement in Portland. Just as quickly, Betts came to see O’Meara as an indispensable part of that push.

“When we first arrived in `75,” Betts remembered, “there were very, very few people that really knew that much about the game. You found that Dennis probably knew more about the game than most people in Portland, at the time. With being at the University of Portland and getting that program off the ground, he was a great candidate for the job at the Timbers and really helped the players and the team get the recognition that soccer deserves.”

“Everybody that got in touch with him,” Betts continued, “and you can look back at all the old Timbers from Mick Hoban and Willie Anderson, we look at Dennis with high regard. He was helping us out not only with the team but also with stuff around town, and was always there if you had a question.”

When, in 1976, the Timbers took part in their first college draft, it was O’Meara who did the work, using his connections in the Oregon college soccer community to scout and eventually choose the players. Before that, O’Meara was playing a prominent role in Timbers’ tryouts – usually held at Catlin Gabel School in the West Hills – organizing the events and helping process the paperwork when he and Hoban weren’t narrowing the player field. Though his title was public relations, and he was only 23 when he came to the job, O’Meara’s skillset made him a de facto technical director in the Timbers’ nascent phase. His job went far beyond PR.

When it came to PR, though, O’Meara shined just as brightly. In the days before email, web sites, social media or newsroom fax machines, O’Meara was tasked with hand delivering the club’s press releases and media advisories, when he wasn’t left with life on the telephone. He forged close relationships with local media legends, like

Oregonian columnist and Oregon Journal sports editor George Pasero, leaving the biggest Portland influencers with easy access to what would, through O’Meara’s work, become one of the Pacific Northwest’s most popular teams.

“I know from having spoken to many of the media people in those days ...,” Hoban said, “just how much they appreciated the quality and the professionalism of the media setup that Dennis had established.”

“Dennis had a great rapport with the press ...,” Betts remembered, before running down a list of local writers O’Meara had helped. “[They] were always asking Dennis for some information. Of course, Dennis gave them the right information.”

The description sounds by the books, but there is nothing by the books about a 23-year-old being a one-man PR department, and still performing well beyond his role. As both soccer conduit and curator of local connections, O’Meara served a truly foundational role for the professional game’s early days in Portland, making it impossible to imagine where the early Timbers team would have been without his skills.

And yet, the Timbers’ chapters are only one part of O’Meara’s legendary contributions.

-----------

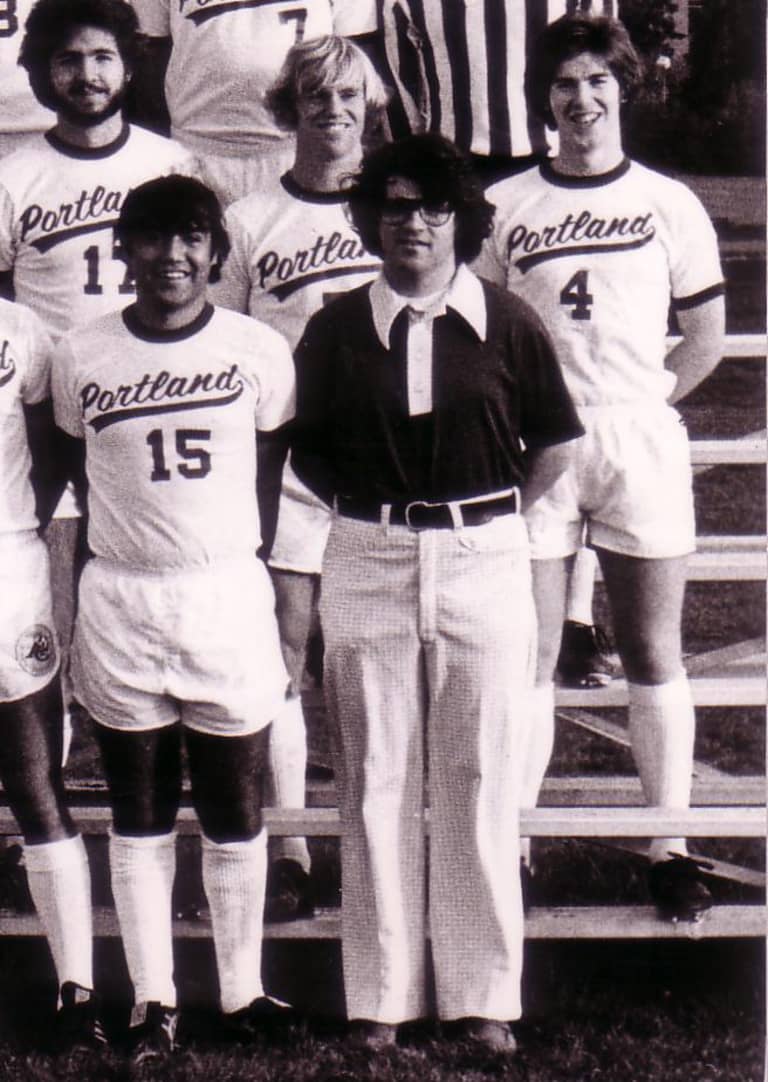

It was up on The Bluff, on the University of Portland campus in northeast Portland, where O’Meara had his first major impact on the local scene. In 1974, at only 22 years old, O’Meara founded the men’s club team on campus, serving as its head coach over the next six years. Though that time coincided with the NASL’s arrival in Portland, O’Meara’s devotion to the Pilots persisted, so much so that when his coaching tenure ended in 1978, he had developed the program into a varsity sport, bringing the team to within one game of the NCAA tournament in his final season.

“He was able to get some of the English players over, involved in the program,” UP alum and longtime benefactor Walt Spitznagel remembered about O’Meara’s early contributions. Spitznagel initially met O’Meara while serving as an AAU basketball coach, for which O’Meara was an occasional scorekeeper. It wasn’t long before that scorekeeper had set a national collegiate soccer powerhouse in motion.

“With the soccer program, England was a powerhouse,” Spitznagel explained. “He got some of their kids to come over, be part of the university. That made them a pretty good program.”

O’Meara founded the program that would eventually be handed off to the legendary Clive Charles, who took UP to full national prominence in both the men’s and women’s game. The men have gone on to make 15 national tournament appearances and two College Cups, while the women have claimed two national titles. Along the way, UP’s program has delivered a series of legendary names to North American soccer, including Christine Sinclair, Kasey Keller, Tiffeny Milbrett, Steve Cherundolo and Megan Rapinoe.

“When he was at the University of Portland, no one really knew that much (about soccer),” Betts remembers. “He even once asked me to come and referee one of his games, which nowadays you couldn’t do that for a university.

“But you were always there because Dennis was willing to help us out, so when he was in need, some of us went over to help with coaching sessions. I’m probably not the best referee in the world, but I refereed one of his games, for him.”

Even after transitioning out of his coaching role, O’Meara would frequent games on The Bluff, often accompanied by Hoban – an assistant on his 1978 team – as well as the other close friends he’d made throughout his time in the game. Yet despite the crucial part he played in the program’s foundation, at Merlo Field, O’Meara remained relatively anonymous.

“We’d go to games at the University of Portland,” Hoban remembered, “and precious few people who were there realized that before the era of Clive at the University of Portland, Dennis had established that thing by his own volition, which actually included Gus Porano from the Timbers’ ownership group, myself, Roger Goldingay, Ray Martin – three ex-Timbers, as well, who volunteered to help Dennis. We volunteered because he was just such a good guy.”

"Dennis was an incredible man who deeply loved Portland soccer," current Pilots men’s head coach

Nick Carlin-Voigt told the university’s website. "For decades he loyally supported UP soccer and will be remembered as an architect in the program's storied history."

Time eventually took O’Meara farther from The Bluff, and Portland in general. Politics, for a time, would take him down to Salem, though much of his time away from Oregon’s northern border would be spent on the east coast, where he had success in the banking industry. “We didn’t know of his financial capabilities until he became a Senior [Vice President] back in New York City,” Hoban said, referring to his time heading the research group at Mizuho Corporate Bank, the world’s second-largest bank. Prior to returning to Oregon in the late 2000s, O’Meara became the first non-Japanese person to hold a senior credit position at Mizuho,

according to the Catholic Sentinel. By 2014, he had retired to Colorado.

In retirement, his ties to UP and Portland soccer gained strength, once more. In 2013, he authored

a detailed history of the university’s soccer history for Portland Monthly, by which time he was volunteer coaching again, at Westside Christian High School. He managed communications and public relations for Timbers legend Jimmy Conway’s testimonial match in 2010 and, in late 2017, coordinated the 40-year anniversary of his 1977 Pilots squad - a team that holds the record for longest winning streak in program history.

As with everything he did in over 40 years of professional life, O’Meara neither sought nor received accolades for his work, much of which was done on a volunteer basis. Just as he did when he oversaw public relations for the Timbers, he saw his job as one that promoted others, even as he played one of the most important parts. Having said so many glowing things about others, he left others to speak for him, with even those who met him late in life finding his presence indispensable.

“Recently, Dennis become even more involved in the program as he supported our strategic plan," Carlin-Voigt continued, on UP’s website. "He and his wife Barbara often traveled to both home and away games, always sending notes of encouragement to the team and coaches … Dennis left a lasting legacy on the program and the players he coached on The Bluff benefited greatly from his guidance."

The commonality among all who knew O’Meara – be it from a Pilot, Timber, or non-soccer perspective – were the descriptions of the man, himself.

“He’s just so friendly,” “Timber Jim” Serrill said, when asked about O’Meara’s most important qualities, as a person. “He was always thanking me for my contributions, which was kind of silly, to me, because I never really contributed to the game. I coached my youngest daughter, Hannah, when she was going through bunchball, but never any kind of serious contribution outside of what I did with the Timbers Army.”

To O’Meara, that didn’t matter, nor did it likely matter that Timber Jim had crafted a legend of his own, even if O’Meara undoubtedly respected those contributions. Person for person, anecdote for anecdote, O’Meara is seen with a quiet gregariousness – a want to acknowledge and embrace those around him no matter their reputations. And he did so without seeking the same in return.

“When he was doing this, he was never looking for the publicity,” Betts explained. “He was looking to give publicity to the game and the players who came in. He never really wanted to be in the limelight.”

“Limelight” was a word that came up often when discussing O’Meara, yet always in the same context. Whatever the limelight accompanied the Timbers’ early days or was cast on UP’s formative years, O’Meara left the light for others.

“Always in the background. Never saw the limelight,” Hoban said. “And was the same for 40-plus years that I knew him.”

Hoban knew O’Meara better than most, yet even with their friendship’s intimacy, the Timbers icon speaks of his former front office counterpart with an air of reverence – a level of adoration that rarely transcends life on and off the field.

“He really was a man of many talents,” Hoban explained. “From my vantage point, he was extremely professional. He was meticulous in his preparation. And he was unflappable. Which, all of those things help you when, in less than three months, you have to put together a professional sports franchise.”

“When you think about Dennis as a person,” Betts said, “he was never the one that wanted to take the limelight, and that’s probably why there are very few people who knew what he did and he accomplished in such a short period of time – not only for the work at the University but also for the Timbers.

“He was one of those guys who did a lot of hard work, the grunt work, and gave people the publicity, and never wanted it for himself. That’s probably why very few people knew or know of Dennis O’Meara.”

“I just think he, in retrospect, typified what’s best about Oregon,” Hoban said, speaking through tears while still coping with his friend’s departure. “He was humble, hard-working, amongst the best friends that a person could have, and welcomed warmly every player that came into Portland during those early days. And everybody that met him – and not just Dennis, but everybody else associated with the club made sure that we felt as comfortable and at home.

“Dennis was the epitome of that sentiment. He was just a warm, kind, giving, caring, selfless individual.”

-----------

They’re the words we want said about us when we’ve gone – the legacy we want for ourselves, without being able to say to aloud. They’re the words you’d want associated with one of your children, and qualities you seek out in the people around you. They’re the stream of consciousness of what a life, fulfilled, would be through the lens of others, yet for those who knew O’Meara best, they’re also rarely spoken, until this last month. With his passing, O’Meara’s story has had a final chance to be told.

Still, as was made clear by those who knew him, Hoban’s were words O’Meara would never ascribe to himself. His time was spent elsewhere: starting college teams at 22; helping found professional teams at 23; moving on from this first coaching job at 27; working in local and state government; making history with international corporations until retirement; beyond that, continuing his dedication to soccer. He lived two, three lives in one, leaving no time to worry about what others thought of any. He preferred others be allowed to think of themselves.

For one day, though, we can stop and think of O’Meara: those who knew him, as well as those who didn’t. Those who never knew his name before now have so much to thank him for, and so much to catch up on. His legacy is over 40 years in the making, and as those who will be in attendance at Ascension Catholic Church will know, the wealth O’Meara gave Portland should not have been overlooked for so long.

He is a legend of Portland soccer, acknowledged as such by his peers, whether those of us who’ve enjoyed his labors knew so or not. As people like Hoban and Serrill would say, O’Meara’s name deserves to be remembered with theirs. And those of us lucky enough to live in what O’Meara’s created should keep his memory close to our hearts, even as, in one of Portland’s secluded nooks, his remembrance will be as solemn as his life’s contributions.

“Hell, my name is up in the rafters,” Serrill said, of his place next to Hoban’s at Providence Park. “I’d gladly take my name down to put [O’Meara’s] name up.”