It was probably before he officially signed, in those weeks where Samuel Armenteros’ capture was as much Twitter rumor as something to count on, that the question was raised for the first time: Can the new guy and the old guy play together? The preseason seemed to hint yes, they could, with head coach Giovanni Savarese occasionally moving to a two-front, diamond-midfield formation as part of his halftime adjustments. Would we see the same look, one that got Fanendo Adi and Armenteros on the field together, come the regular season?

The Portland Timbers’ slow start scuttled that, with Savarese having to break things down and start building them back up after his team’s first two matches. The move to a 4-3-2-1 formation seemed to commit the Timbers to a one-front, especially once the team got on a roll. Over the team’s ongoing eight-match, MLS unbeaten run, there’s been a certain “if it’s not broken” logic to sticking with the approach.

Friday night, however, gave Savarese an opportunity to experiment. It wasn’t MLS play. It was U.S. Open Cup, and although the Timbers want to do well in the competition the tournament a sandbox, of sorts. Two weeks ago against San Jose, Portland threw Jeremy Ebobisse, Marvin Loría and Renzo Zambrano into that playpen, starting each through the middle of a formation Portland thought it would play this season, a 4-2-3-1. And last week, the team reverted to that preseason look that captured so many imaginations, one that got both Adi and Armenteros on the field, together, in their best spots.

The backstory

The history of that “diamond” formation, traditionally referred to as a 4-3-1-2, begins in most places with the desire to pull an attacker back from the forward line in a 4-3-3, not only to get a skilled player closer to the ball but to take advantage of how defenses had come to defend that three-man attack:

In the abstract, the ability to connect through this withdrawn forward allows the three true midfielders to continue with their more defensive responsibilities. And with the increased athleticism coaches saw from forwards, as the game evolved, teams were able to maintain the same attacking threat up top while deploying fewer forwards. Either opposing teams would have their center back follow this new, attacking midfield player, thus opening up space higher up the field, or they'd let that withdrawn player drift, allowing him to roam unmarked through open spaces on the field.

In a way, the trequartista’s role, as it came to be called in some cultures, was the first that had neither primary goal-scoring nor goal-preventing responsibilities. Just be there to float, connect and create, was the mandate, eventually. Help the levels around you do their jobs.

For the Timbers, Friday’s formation served the same role, only changing the numbers slightly from what they were playing before. In the 4-3-2-1, many of the team’s principles were identical, especially defensively. The only real difference was taking one of the team’s tandem trequaristas–in this case, Diego Valeri–and moving that positions to the forward line.

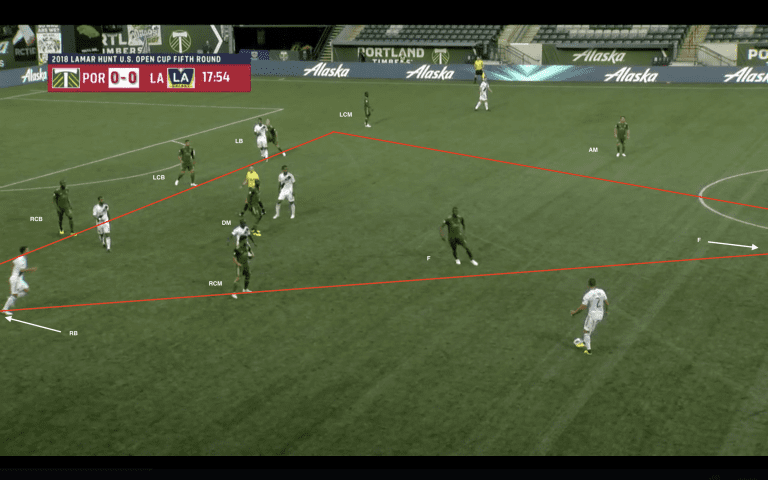

The base shape defensively, however, didn’t really change. You can see the Timbers forming their line along the side of their pyramid, just as they did before, trying to keep play to the outside. Often, Adi or Armenteros would drop from their high deployment, to be in position on the weak side should the Galaxy try to switch play. If that happened, the look was the same: a line of fullback, midfielder, attacking mid and forward, all pushing play to the touchline.

There are things Portland does that deviate from this pure diamond shape. For example, look where Diego Chara is situated, above. He's tracking LA's widest attacker all the way into the back line, even on the weak side of play. Often, you will see the team's other central midfielder (on Friday, it was Andrés Flores) do the same, even when they're on the strong side of play. The team isn't committed to a pyramid shape, at all costs. It's just the base from which they make their decisions.

It’s worth a pause here to talk about how this approach differs than a lot of teams’, on a basic level. It’s not unique, but in our article earlier this season about the Thorns’ pressing, we outlined the ideas of triggers and traps. Most teams are trying to push play to certain places where, once there, they can pressure them into turnovers. Sometimes this happens along the sidelines, but often, you see teams try to pinch fullbacks or wingers, force an ill-advised ball back to the middle, and rely on ball-winners in midfield to ignite counterattacks.

Right now, the Timbers’ core principles are a little different. If you try to break through the walls of their pyramid, absolutely, players like Chara and Cristhian Paredes are going to turn you over. But if you just try to play around the formation, they’re going to keep you wide, as a core principle, and force you to work back around that long arm side of the formation.

A different attacking look

The major difference for the Timbers, with their formation change, was in how they attacked. As discussed in the wake of Friday’s game, having Armenteros to run off of Adi allowed Portland to play directly through a target man instead of relying on him to, with his off-ball movement, create space for the team’s two creators. Armenteros, who has played most of his career at the top of very Dutch implementations of a 4-3-3, was freed from his hold-up responsibilities to run off Adi, and not in the same way he’d do if he was playing atop Portland’s normal formation. When he wasn’t dragging defenders from dangerous areas, he was hunting second balls or otherwise taking advantage of the attention the Galaxy gave his more physical partner.

Then there was the effect on Sebastián Blanco. Often, the Timbers’ creator was put in a position to be a fulcrum out of the back, mostly when the team was having to build play in a more methodical manner. Having two attackers up top freed him to seek the ball out, knowing he was the one player at the level tasked with doing so. But when the Timbers played direct, they eliminated Blanco’s responsibilities as the team’s trequartista, freeing him to be a type of secondary run-maker, keying off Armenteros’ and Adi’s movements.

Of course, there was no place where that was more evident than on the night’s only goal, a play that, straight from the training ground, saw Blanco take advantage of the action around Adi and Armenteros.

The most interesting part of Friday’s formation isn’t that it largely worked; rather, it’s the implications that success has on the team, going forward. Not only does this provide the season’s second significant wrinkle in shape but it also prompts questions about how players could be deployed, in the future.

If playing directly to Adi is something that would work best against a team crowding the middle, might we see a player like Valeri become more of an Armenteros mover and let Adi’s play dictate their movements? Might we see somebody like Andy Polo take up one of the forward positions, knowing that off-the-ball movement will be more important than hold-up play?

Or, maybe the obvious is the angle, here: This gives the Timbers a way to play Adi and Armenteros together. It also gives them a way to change things up against defenses that are still tailoring their look toward the Timbers’ expected approach.

As the season goes on, and the games start to pile up, chances to rotate Adi, Armenteros, Blanco and Valeri will be harder to find. It will be nice for Savarese to know that, regardless of which players are ready on a given night, he’ll have a formation to fit the personnel, whether that formation’s a 4-2-3-1, 4-3-2-1, or, as of Friday, a 4-3-1-2.