Brad Cloepfil is an internationally renowned architect who has deep Oregon roots. Growing up in Tigard and later studying architecture at the University of Oregon, Cloepfil and his firm, **Allied Works**, started out designing residences and buildings in the Portland area. One of his firm’s first big commissions was the **Wieden+Kennedy world headquarters building** in Northwest Portland – a building that helped spark the transformation of the Pearl District during the late-1990s.

He went on to design numerous art museums, cultural institutions and creative buildings across the world including the **Seattle Art Museum**, **Pixar Animation Studios** in Emeryville, Calif., the **National Music Centre of Canada** in Calgary, **the Museum of Arts and Design** in New York City, **the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis** and **the U.S. Embassy in Mozambique** to name but a few.

But the opportunity to design an expansion to the historic Providence Park back in his hometown was one Cloepfil and his firm could not pass up. Having never designed a stadium before, the prospect presented an entirely new challenge and one that first came about over a lunch in the afterglow of the Portland Timbers’ 2015 MLS Cup winning season.

Now three and half years later, the rebirth of Providence Park is nearing completion with 4,000 new seats being built on a new eastern side with a soaring vertical stand, a new roof, new premium areas, spectacular views of the pitch (and the city), a new sidewalk colonnade and more. It’s been a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for Cloepfil and we sat down to hear about how it came about, his personal history with the game of soccer and the special alchemy and magic that goes into taking on the design of a truly classic American soccer setting.

Courtesy Allied Works

Brian Costello: I think the place I was going to start was sort of, you’ve designed museums and cultural institutions and educational spaces and residences, but as far as I know, you’ve never done a stadium.

Brad Cloepfil: No. Nope.

Costello: How did you get involved in designing the Providence Park expansion? How did that process come together?

Cloepfil: Right. It’s kind of a good story. I think it could have only happened in Portland, Oregon too.

So, Timbers won the MLS Cup. I reached out to [club president of business] Mike [Golub] and said, “I’d love to take you to lunch and just bask in the glory.”

I took him to lunch and he told me all the stories, and it was really amazing. And then we were just talking and it was like… There was no agenda too, to be very clear here. So we were talking and I said, “So what are you going to do now? The league is growing so much, you’re going to have to move to the suburbs and build a 40,000-person stadium to pay for all this.” And he goes, “Okay. When’s it happening?” And I was saying it half in jest but half not.

He goes, “Oh no, we would never do that. Never do that. They’d have to stay in the city.”

And I thought, well, that’s fantastic. That’s great for Portland.

And then I said something, “Well, have you guys figured out how many seats you can get in there?”

And he goes, “Well, we’ve studied various plans on the south side of the stadium, but haven’t found a solution that works right nor yields enough new seats.”

And I said, “Well geez, I’d take a look and see how many seats… I’d do that.” And his eyebrows kind of go up and he says, “You don’t design stadiums!” I go, “I know. But we’re creative, and we might be able to find something.”

And then I told him, “I would even do it for free.”

Costello: There you go. That’s a good price.

Cloepfil: And I just said, because it would be fun, frankly. Seriously. This is out of being a fan, and from Portland, and everything. And, you know, my daughters all played soccer. I have a daughter playing professional soccer. [Ed. Note: Georgia Cloepfil has played in Australia, Korea and Lithuania.]

We kept talking about it. I told him, “I’m serious, I would do it. It’s something that would be really fun for us. See what we can find.”

Anyway, a couple of weeks later, I think he’s in New York, he calls me up. I was in Oregon. He says, “Were you serious?” And I go, “Yeah, I was serious. SERIOUS, serious. Free. Good.” I said, “We’ll spend a month or two researching, trying to figure it out, everything.” And then he says, “Okay.”

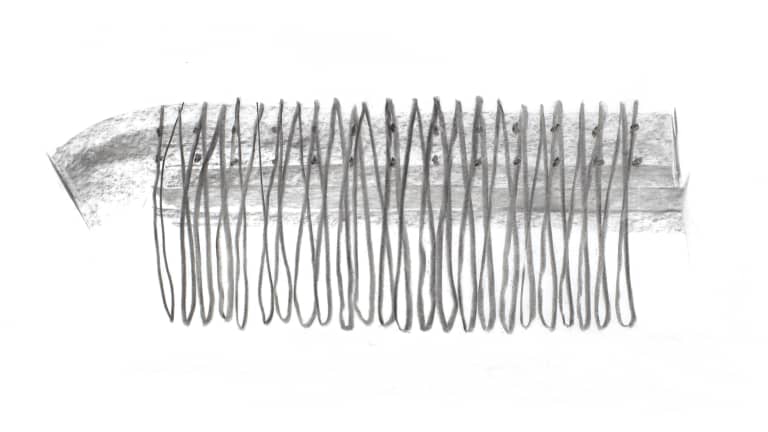

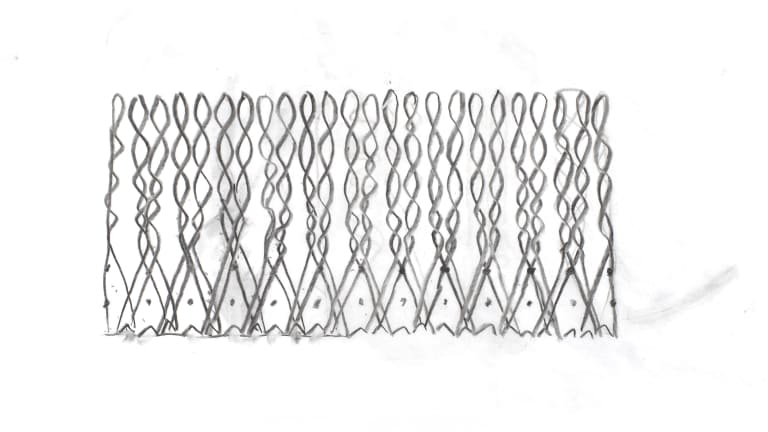

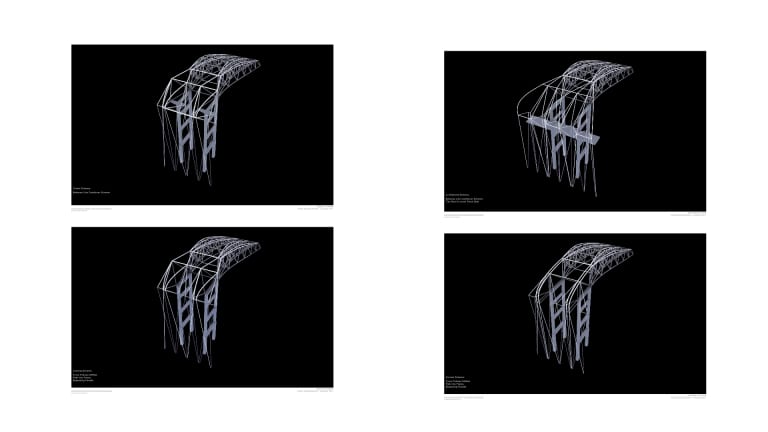

Images courtesy Allied Works

I had no idea what we could find or not find. We did tons of research into every soccer stadium we could, from Santiago Bernabeu Stadium to Old Trafford. I mean, everything. We got drawings offline, of the rakes, of the seats, of the view corridors. Everything. We did a month of research, and then started proposing stuff. We found that one stadium, it’s for Boca Juniors.

Costello: **La Bombonera**.

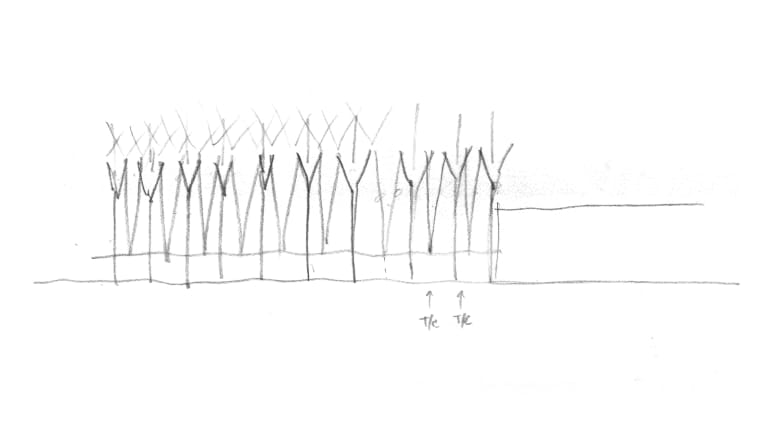

Cloepfil: Yeah. La Bombonera. And the stadium is landlocked in a city, like we’re in, and it has a narrow side like we’re in. **And it has this vertical tray of seats that goes straight up.**

And I thought, that’s it. And so we tried it and we ended up getting 4,000 seats, and not losing seats below. And then the theory was [the construction] could happen during the season. The first year. All that construction happened during the season so it didn’t disrupt. So we actually came up with something that had some common sense and was kind of smart. And then [club owner and CEO] Merritt [Paulson] and Mike ran the numbers and we thought, this can have a huge impact.

Courtesy Allied Works

Cloepfil: When we pitched it, we met with Merritt and I told him we’re going to create the Globe Theatre of soccer. Because if you know **the Globe Theatre, it’s a theatre in the realm of Shakespearean theatre**.

**It’s just vertical galleries of people kind of hanging over the stage.** And I said, “We’re going to create the Globe Theatre of soccer.” And I guaranteed Merritt 10 more wins this season if he built this.

Costello: (Laughs) That’s a pretty big guarantee.

Cloepfil: Yeah. (Laughs.) I’m throwing irresponsible statements all over the place. But, you know, I just thought the energy of the stadium when that wall of people on that side that was kind of open, it’ll be amazing.

Costello: You’ve said you’ve been to Timbers games and your daughters had played soccer. Were you a hardcore soccer fan before this? Was it something you kind of had grown into? What’s your relationship, would you say, with the game

Cloepfil: When I was in my freshman year in college, this team called the Timbers showed up [in the North American Soccer League]. It’s funny. I played American football, a lot of my friends played basketball. We were serious jocks on a terrible high school team in Tigard. (Laughs.)

Anyway, so we kind of fell in love with soccer. We’d never been exposed to it. This was mid-seventies.

Costello: 1975 is when the team came in the NASL.

Cloepfil: Yes. We started going to games and then we started playing pick-up soccer. And it was really fun. And then The Timbers beat Seattle in the playoffs. We went to that game.

Then when I had my daughters – I have four daughters – and those girls kind of grew up with when the U.S. team won the first World Cup and Olympic gold era. And then all those girls from University of Portland, **Shannon MacMillan** and **Tiffeny Milbrett** – they all went to UP. So then we’d watch all the UP games, the quality of women’s soccer in Portland at that time was crazy.

So my girls grew up around that, and my ex-wife was a track star at University of Oregon. So, you know, we had a sort of jock roots and these girls all grew up playing that. And then that really got me addicted.

And so all along I’m following the Timbers and seeing games when I can, even when I didn’t live in Portland. Just a long relationship, I would say. I mean, I don’t have a Timbers tattoo on my butt or anything. (Laughs.)

Costello: If we’re talking about Providence Park as sort of akin to what Lambeau Field is to American football, or what Fenway Park is to baseball, how did you figure out, or did you try to figure out how to take some of that spirit of the stadium and its history, and put it into the design?

Cloepfil: Yeah. It’s holy ground, isn’t it?

Costello: Yes.

Cloepfil: It is daunting. It’s raw. It’s not fancy. It’s transparent, so you can see through it, you can see people. The original building was raw concrete. This is raw concrete. It has that kind of elemental thing that Oregon’s all about.

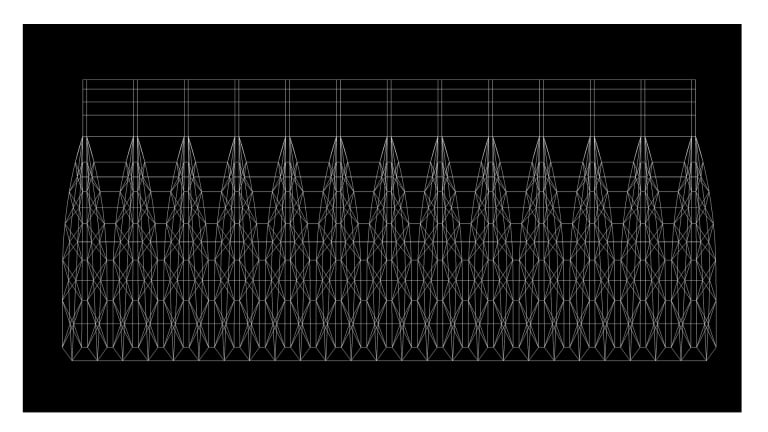

It’s really about the game. And I just think, to me, my joke about 10 wins is not a joke. I think what we’re doing is we’re creating the intensity, or we’re amplifying the intensity of the fan experience. It will just be unbelievable. The immediacy to the field.

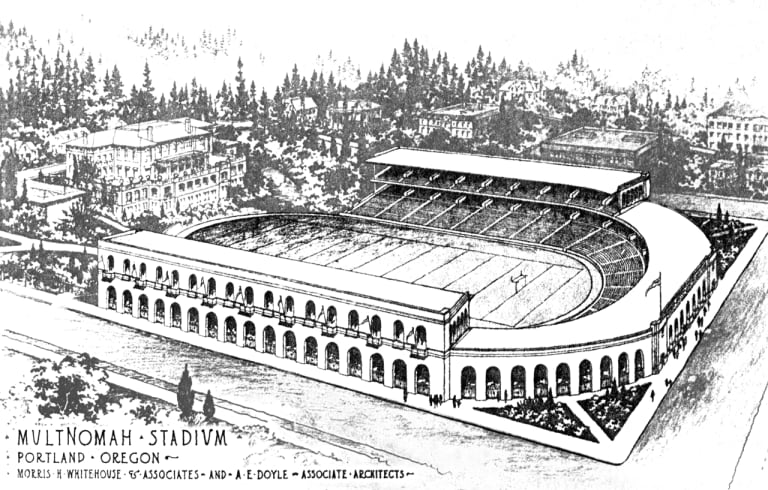

And then we’ve got a historical image – I don’t know if you saw that – where they had planned a two-story [on the east side].

Costello: The original A.E. Doyle design from 1926? Yeah.

Cloepfil: Yeah. We found that in our research, and that was really encouraging. It was a two-story piece along the street there. So, yeah, that’s kind of it. Transparent, kind of simple, elemental. It’s really for the fans and the game.

Costello: Are there any sort of nooks and crannies or things that you like? Like secret spots, or spaces that you think are interesting?

Cloepfil: I just walked it for the first time in a few months and there’s all kinds of little discovery spaces. The first thing is, you’re just right on top of the field. It doesn’t matter what level it is. It’s just amazing. Even when you’re on the third level, you’ll see the entire run of play. That’s one thing that’s amazing.

In fact my favorite seats, I want to get seats on the second level because I think that’s the sweet spot. Because you’re up high enough you really can see everything; all the space, all the ball movement.

At the ends of the seats, both the north and the south ends, there’s these overlooks and overhangs – especially to the north end – where you really can stand out there.

I think the third floor with the views of Portland, that kind of overlooks some balconies that look back at the city and over the field [is also great].

Costello: You mentioned finding the A.E. Doyle sketch, and I know you’ve designed this sort of colonnade on the outside too that works with the sidewalk. How much of the history of both the building the neighborhood played into the design?

Cloepfil: Moving out over the street was huge – to arcade the stadium over the sidewalk. So that when you’re walking down the street during game day you’re really in the stadium. You’re basically in a concourse. The only thing separating you is the transparent fence. So you can see into the field like the old days. You can see down to the pitch. It’s an amazing urban experience.

Courtesy Allied Works

Now [the city] was a big thing for us too, because at the same time this thing is going up and overlooking the field, you’ll be able to see people from the city. You’ll see people on all the different levels. All the action and activity. And people milling around and looking over the city and the street. It creates a connection to the city. It’s just going to be a wall of people and energy. That’s what it is.

Costello: I grew up in Minneapolis and I remember going to the original, though now dismantled, Guthrie Theater with Ralph Rapson’s design.

Cloepfil: Oh, wow. You are an architecture fan. That was a cool building.

Costello: It was a great building. **It had that permeability with its exterior** where it would **frame people in the windows and the walls so that if you were outside, you were seeing a “performance” of people in the lobby.** And I think there is a lot of crossover between that building and this design.

People talk about the players. Did they perform well today? How did they perform? What was the team’s performance like? There’s a performative aspect certainly to an athletic performance, just as there is to an artistic performance.

Cloepfil: Oh, no question. Again, back to the fan experience. You can take anybody. I took my mom, who’s not a soccer fan, to a game, and it’s moving. It’s just such a powerful, moving experience in Providence Park. And what you were starting to say too. I mean, one of the things that struck me when I was [at the stadium] – and I kind of knew it intellectually when we were designing obviously, – is that it’s so urban. It turns that stadium into this intensely urban, densely packed vertical thing. Not only because you’re doing all this work to the entire stadium, but [the design] will change the entire vibe to be even more intimate and intense. I think that’s the exciting part.

I mean, for me, I feel incredibly lucky that Merritt chose to do this with us. To your point, having never done a stadium, letting us come up with these ideas and create this thing. I feel incredibly lucky. And I have learned. We as an office learned so much. I can tell you one thing we learned, and I say this to people, stadiums are a lot harder than art museums, I’ll tell you that. They're a lot harder than art museums.

Costello: Why so?

Cloepfil: I’m joking, but they’re just so different. I mean, art museums, on one level are – you’re creating beautiful but you're just creating a series of empty rooms.

They have to be beautifully proportioned and have beautiful light. They have to be amazing.

But the movement of 4,000 people, the sight lines, the distance from the field, the concourses…It’s an entirely new thing that we’ve learned.

And there’s no rules. That’s one of the things we found. Every stadium, it doesn’t matter how famous, it doesn’t matter how simple, has different sight lines, different breaks, different spacing. So it’s basically an alchemy. It’s witchcraft, as far as I can tell. You stir the pot and you hope you have the magic.

Courtesy Allied Works

Costello: And if you’re designing an empty room in a museum, here the empty room already exists – it’s the pitch. You’re trying to figure out how to get people in to watch it, right?

Cloepfil: Right. See, that’s the thing. That’s a good lead in. Architecture for me, it’s never the subject. You want it to be beautiful, you want it to be a place people want to be. But to me, what you want to do, you want it to charge the space. And I talk about that with art museums. You wanted to give the museum a charge but you don’t necessarily even want to notice it. You just want to feel that energy of beautiful light, beautiful proportions and it’s the same there.

You want the stadium to be full of a kind of anticipatory energy. That’s what you want. You want it to just build anticipation just being in there.

And the really good stadiums – I mean, all stadiums do that, to a certain extent – but the really good ones, you walk in and you kind of catch your breath almost. That’s what you want.

Costello: Because you’re excited for that moment. You don’t know what’s going to happen.

Cloepfil: Exactly. Actually, it’s amazing. That’s the most amazing thing about sports stadia. And you walk through a tunnel or you walk out and look over the field and you see the people.

That was also really important to us to have all those breaks on the east side. That you not only see the field, but you could see all the people. So you really feel like you’re in it with them. That’s really, really important. I think that’s incredible. In fact, that little north overlook that’s when you look back, you look over the existing seats, and you can also look back at the new seats and you really see the entire 25,000 people. That’s an amazing spot.

Costello: What does it mean to be able to design something like this, and in such a public space, in a place you grew up?

Cloepfil: It’s amazing. I think about this a lot actually too, because you’re right. You know, we did the National Music Centre of Canada, which is a building that aspires to manifest the musical history and aspirations of a country. So we get to do these things.

But if I was going to do one project in Portland, Oregon – [be it] the art museum, a new performing arts building – but what would really mean the most to the city?

Courtesy Allied Works

I would contend that the Timbers are the most beloved cultural institution, and I’ll call it a cultural institution or civic institution, in the city. By far. And so to get to do that, it’s the right project for me, outside of my passion for soccer and the history and all the other stuff. But if you got to manifest the spirit of a place in the city I grew up in, it’s the perfect project. We’re so lucky. So incredibly lucky. And the fact that it’s two blocks from my office is the mindblower. We get to watch it go up. And it’s such a sophisticated thing structurally, with the steel structure tying down to the streets, the enormous cantilever. There’s a lot of learning in it, so it’s been great fun.

Costello: I think, like you say, as a space, as a building in the city, as a central gathering spot and access to things revolve around on a game day, it’s going to be really interesting.

Cloepfil: What’s amazing about Providence Park too is, you know, we looked at the old stadium that Man City had – Maine Road – before they built Etihad Stadium. And I don’t know if it was Craven Cottage or one of the other ones we looked at, but they had the old covered bleachers, and then each side of the stadium was a different era. Or there was like two historic sides and then two new sides. And I just thought that moment in the Premier League before they started doing mega stadiums, tearing [the old ones] all down, I thought that was the magic for me. Because you got the historic piece, and the new pieces. And you could kind of feel the whole history of the club. I mean, that’s the gift of this stadium to the Timbers – we have this history.

We have a near hundred-year-old stadium that no other soccer club in North America has. So we have that Old Trafford, [that] Craven Cottage. We have that gift of history. I also think the old and the new in the stadium is the kind of charge that really gives it more gravitas. It’ll make the old parts feel even more authentic, and the new parts more energizing. I cannot wait. I just can’t even imagine. I’m going to cry like a baby on the first day, let me tell you that.

Only if they win. (Laughs).

Courtesy Allied Works